By Andrea Alexander, Rutgers University Communications and Marketing

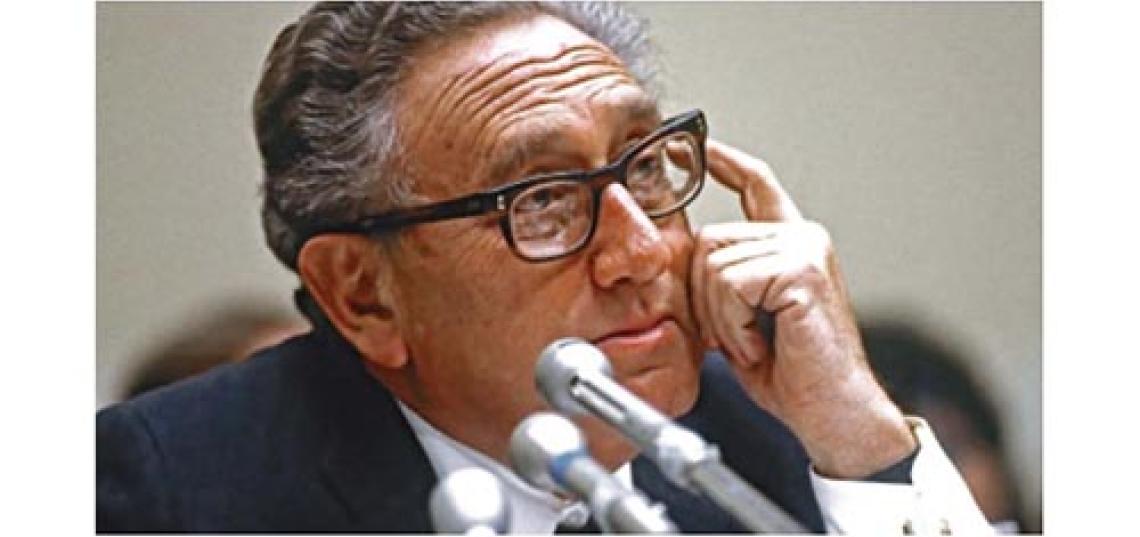

Henry Kissinger, who served as secretary of state under Richard Nixon during the Vietnam War and continued to advise American presidents for generations, is both a revered and reviled figure credited for his unparalleled influence over U.S. foreign policy.

The only person ever to be White House national security adviser and secretary of state at the same time, Kissinger died yesterday at the age of 100.

David Greenberg, a professor of history and journalism and media studies and author of "Nixon's Shadow: The History of an Image," talks about the highs and lows of Kissinger’s decades of public service.

Henry Kissinger was a figure of contradictions. He shared a Nobel Peace Prize for his role in negotiations to end the Vietnam War, but he is also accused of being a war criminal for his decisions during the conflict. Can you explain the dichotomy?

When major wars end, it’s not uncommon for diplomats to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, F.W. DeKlerk, the former president of South Africa, and Yasir Arafat, former chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization, all won the Nobel prize, and all had tremendous amounts of blood on their hands before they made peace. And while Kissinger’s Vietnam policy was certainly disastrous – for the U.S. and for the people of Vietnam – the label of “war criminal” is a fundamentally unserious one. It’s telling that it’s leveled by people who have a beef with Kissinger but not the man who designed the policy, President Nixon, or the ones who carried it out, his defense secretaries. Because of Kissinger’s fame and charisma, he drove people into conniptions and caused them to veer into implausible hyperbole.

How does his role in shaping world affairs decades ago affect foreign relations today?

Mainly his role in forging a relationship between the United States and China has continued impact. Again, the foreign policy was Nixon’s, not Kissinger’s. Kissinger carried it out. But the decision to welcome China into the family of nations had enormous repercussions, ones we are still feeling today. He also had, in other respects, what you might call a negative influence. His hard-headed “realpolitik” was seen as so heartless and misguided in many places that he opened the door for a reassertion of the role of human rights in foreign policy, which most subsequent presidents have recognized as important.

How was he never tainted by the downfall of the Nixon administration, and why was he still looked up to in certain circles?

Kissinger was up to his neck in Watergate yet never suffered much for it. It’s astounding. His illegal wiretaps on journalists and White House staffers were some of the earliest crimes of the so-called “White House Horrors.” One reason was that he was amazing at courting the press and ingratiated himself with Washington insiders in ways that Nixon never did. The other was that as Nixon sank into depression during Watergate, people realized that a few “adults” were needed in dire times – so people like Kissinger were deemed necessary.

Why did presidents long after Nixon continue to seek his advice and counsel?

There is no question that he was an intelligent man with rare experience in foreign policy, so it is not surprising that he was consulted by subsequent presidents. However, he often gave bad advice – as when he told George W. Bush not to withdraw troops from Iraq even after Saddam Hussein had been deposed.

Overall, what do you think his legacy is and what should he rightfully be remembered for?

He did not invent the realpolitik style of foreign policy – subordinating concerns of human rights to cold calculations of national self-interest – but he became its best-known exponent and practitioner. But if I could sum him up in one word, it would be "overrated" – overrated as a scholar, as a national security adviser, and as a “war criminal.”

Learn more about the Journalism and Media Studies Department at the Rutgers School of Communication and Information on the website.

This article was originally published in Rutgers Today on November 23, 2023.

Image: Mark Reinstein/Shutterstock