She was in Romania in 2007 when she first discovered vernacular museums, initially as a tourist, and later as part of an ethnographic fieldwork course. After that, Cheryl Klimaszewski, Ph.D. ’20, became so fascinated by exploring and understanding these homegrown, grassroots Romanian museums that she ultimately wrote her dissertation about them.

“My doctoral dissertation study grew out of these unexpected encounters with personal interpretations of the museum form,” Klimaszewski said.

Klimaszewski’s dissertation, titled "An Ethnographic Study of Romanian Vernacular Museums as Spaces of Knowledge-making and their Institutional Legitimation," was recently honored by the Association for Library and Information Science Education (ALISE) who awarded her second place in the Jean Tague Sutcliffe Doctoral Student Research Poster Competition.

Professor Marija Dalbello, Klimaszewski’s dissertation advisor, said, “I am pleased that Cheryl’s dissertation research has been recognized by the jurors of the Jean Tague Sutcliffe competition, especially because of its grounding in innovative ethnographic and visual analysis approaches to study grassroots museums developed in local communities and extensive fieldwork she has undertaken in Romania. The award gives visibility to her rich and innovative project."

My doctoral dissertation study grew out of these unexpected encounters with personal interpretations of the museum form

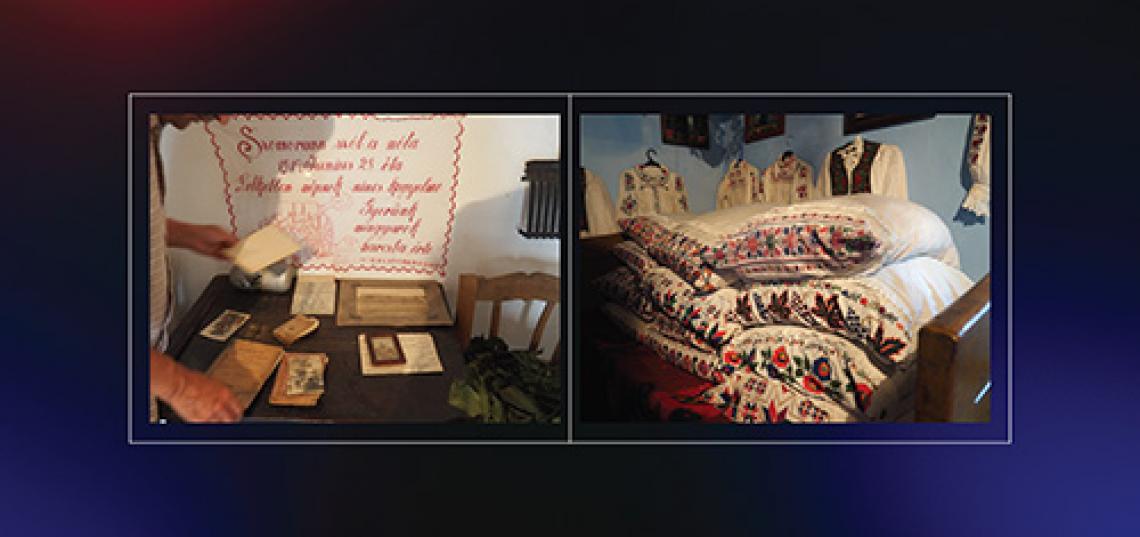

Representing collections that are personal or part of a larger community, anyone can create a vernacular museum. They can be a collection of anything, and they don’t need to conform to museum rules or organizing principles. Vernacular museums are similar to vernacular languages in that they reflect local customs in a way that “formal” dialects of languages don’t. Klimaszewski borrows this term from cultural studies scholar Maja Mikula, who has employed it to foreground the domesticity of museum practices as they are enacted in the space of a home.

The reason it is important to understand these museums, Klimaszewski said, is because “Romanian vernacular museums are personal museums created by private citizens within or adjacent to their own homes or family properties. The people who make such museums are passionate about their museum creations and about ‘saving’ objects from the past. Their collections are often built from discarded or unwanted objects salvaged from abandoned houses or even the trash. They see value in these objects, and they want to convey their knowledge about the past to their visitors. The grassroots perspectives on history, heritage, and the past that they provide are an example of ‘democratizing the museum’ relevant to new museology and more recent movements towards decolonizing the museum.

“The group of Romanian vernacular museums I studied were part of a (now defunct) national-level association of 24 museums that went by the acronym RECOMESPAR. This association came about because museum professionals from the National Museum of the Romanian Peasant in Bucharest had been encountering more and more of these kinds of personal museums during their fieldwork throughout the late 1990s and 2000s. These expert museum practitioners created a cultural program called the Village Collections Programme that sought to increase the visibility of these small, private museums that they often termed local museums and village collections. The Village Collections cultural program ran from 2008-2013, somewhat concurrently with Romania’s accession into the European Union in 2007. So, the appearance of these homegrown, grassroots museums has been happening during a time of extensive economic, political and social change in Romania. And it seems that in this period, collecting and displaying objects from the past within one’s own personal museum and then sharing the museum with others has become a way for some individuals to respond to the scope and scale of these changes and their effects on everyday life.”

After having made several trips to Romania following her initial trip in 2007, it was while traveling there in 2018 to conduct research for her dissertation that Klimaszewski said she was surprised by “the number of new or unexpected museums that I found while traveling between the planned study sites. The vernacular museums chosen as study sites tended to focus on the everyday life of the peasant and featured objects that reflect village life. The other museums that I discovered focused on things like daily life under communism, amateur filmmaking, woodworking, the life of a communist dissident, satirical art and family history. This shows that more people are taking to this trend of do-it-yourself museums and how the museum is employed as a communicative form.”

Asked if she found vernacular museums “off the beaten path,” Klimaszewski said, “The museum makers I interviewed were often trying to capitalize on increasing or potential tourism development that might revitalize smaller towns and rural villages, so perhaps describing them as being located along ‘newly beaten paths’ is a better way to say it. The museums were most often found within private properties located in villages, adjacent to or overlapping with their own homes and living spaces. Instead of tearing down an older house, the families would build a new, modern home and then repurpose the old structure as a museum. Some even relocated older traditional homes from other areas to their properties to preserve them as well. From the visitor perspective, entering a vernacular museum meant an immersion within a whole sensory environment, with the museum displays extending beyond static objects formally displayed on a wall or under glass vitrines.”

The vernacular museums chosen as study sites tended to focus on the everyday life of the peasant and featured objects that reflect village life. The other museums that I discovered focused on things like daily life under communism, amateur filmmaking, woodworking, the life of a communist dissident, satirical art and family history. This shows that more people are taking to this trend of do-it-yourself museums and how the museum is employed as a communicative form.

One of the features that distinguishes Romanian vernacular museums from institutional museums, Klimaszewski said, is the personal tour. “The highlight of a visit to a Romanian vernacular museum is the personal tour given by the museum maker, which provides visitors with a unique experience. The visitors I spoke with as part of my study emphasized how their vernacular museum visits stood out because of the person-to-person connection created with the museum maker during this tour.

“These museums also provide a reason for visitors to stop in villages or towns they might not otherwise. The idea of the museum as a familiar institutional form is the draw but the personal and intimate nature of the museum tour, guiding visitors through the space of a home, contrasts with visitor expectations. This contrast seemed to lend a feeling of authenticity to the whole experience which, in turn, enhanced the meaningfulness of the museum encounter. Also relevant in our ‘post-truth’ era, the focus of these museums was not on presenting some definitive or authorized History or Truth. Quite the contrary, each visit immersed me in the maker’s interpretation of the past as they guided me through their museum space as a world of living evidence. I was welcomed as a guest in their home and often treated to traditional Romanian hospitality (complete with coffee and homemade baked goods). This full-bodied immersion in the museum space was a way of ‘being there’ within a nuanced and intimate relationship in the past, versus simply ‘knowing about’ Romanian history from an abstract intellectual distance the way I might absorb it from a book or more formal museum exhibit.”

Employing an ethnographic research approach, Klimaszewski explained, is how she conducted her research. She said, “I combined aspects of autoethnography and the use of visual data combined with textual and visual analysis. My main sources were each museum maker’s tour narrative, which I audio-recorded while I photographed what I was seeing in response to the museum maker’s words. Analysis involved marrying these notable moments of said + seen as examples of relational knowledge-making. As a visual thinker also trained as a photographer and artist, incorporating my way of seeing into my analytic framework was essential for me because the immediate experience of these spaces hinged on their visual and sensory impacts. In addition to analyzing the images, audio recordings, interviews, and fieldnotes created during my month of field study, I also examined numerous cultural program and policy documents and related websites to track the development of this set of Romanian vernacular museums within the EU and Romanian heritage contexts as they were framed in policy.”

Working with a translator was also necessary, Klimaszewski said. “I have a wonderful working relationship with a Romanian colleague who is a cultural anthropologist. She was able to accompany me on field visits in 2014, 2016, and 2018 to act as an interpreter and also to provide insights as a cultural insider as well as a scholar. This allowed me to access various levels of meaning within the narratives, employing her ‘insider’ as well as my own ‘outsider cultural perspective.”

My main sources were each museum maker’s tour narrative, which I audio-recorded while I photographed what I was seeing in response to the museum maker’s words. Analysis involved marrying these notable moments of said + seen as examples of relational knowledge-making.

Though she recommends traveling to Romania to explore vernacular museums if possible, Klimaszewski also notes that there are many similar places located in the U.S. She suggests visiting them because it’s fascinating “to seek out sites like vernacular museums as a complement to (or even instead of!) more commodified travel or museum experiences. As I’ve continued to travel in the U.S. while also completing my dissertation research, I’ve grown to see many analogs between vernacular museums and the sorts of roadside attractions that one can find on the websites Atlas Obscura or Roadside America. I highly recommend that people search these sites to seek out the kinds of offbeat, unexpected, or quirky museums while they are traveling (or that may even exist closer to home). People should visit these more idiosyncratic attractions and consider them as meaningful in their own right.”

In the future, Klimaszewski said she hopes to continue her work in Romania. “My last fieldwork visit was in June 2018,” she said. “I do hope to return to Romania once pandemic restrictions are lifted and it is safe to travel again. Even before the pandemic era, these museums were a labor of love for their proprietors and once the proprietor was no longer able to care for the museum, it would likely become defunct. So following the longevity of these transient institutions has always been an interest. I would like to understand what it means for a museum to be something that has a lifecycle and that is not ‘for all time.’ Now, it will also be important to assess the long-lasting impacts of the pandemic on such unofficial institutions that often rely on cultural tourism for their relevance. Whether these kinds of museums can fill a gap that might be left as institutional museums also face tremendous challenges is also another interesting aspect to investigate.”

More information about the Ph.D. Program at the Rutgers School of Communication and Information is on the website.

Images: Courtesy of Cheryl Klimaszewski, Ph.D. ’20