October has arrived, and across the U.S., stores selling Halloween merchandise are also stocking their shelves with Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) decorations, such as plastic marigold garlands and manufactured sugar skulls painted in joyful pinks, blues, yellows, and greens.

While most Americans are likely accustomed to seeing the colorful Day of the Dead decorations, many are probably unaware of how Dia de los Muertos evolved into a popular holiday in the U.S., both as a spiritual and cultural celebration, as well as a lucrative commercial one.

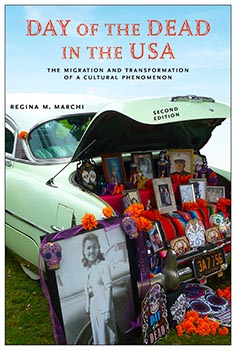

"For Chicano artists in the 1970s, celebrating an indigenous Mexican ritual in an Anglo-dominant country was an act of political resistance as well as an act of cultural pride," said Professor of Journalism and Media Studies Regina Marchi, author of the award-winning book "Day of the Dead in the USA: The Migration and Transformation of a Cultural Phenomenon, published by Rutgers University Press (2009; 2022).

SC&I spoke with Marchi to learn more about the historic, cultural, and political significance of Day of the Dead in the U.S.

Why has celebrating the Day of the Dead become so popular across the U.S. over the past 50 years, particularly with non-Latino populations? Do you think it may one day be celebrated as widely as Halloween?

Why has celebrating the Day of the Dead become so popular across the U.S. over the past 50 years, particularly with non-Latino populations? Do you think it may one day be celebrated as widely as Halloween?

RM: I’ve actually asked hundreds of people the same question. The answer I get is usually the same. Besides the colorful nature of the holiday, with its bright orange marigolds and multi-colored “papel picado” decorations, and besides the fascination people have with sugar skulls, deep down, many people in the U.S. are drawn to the idea of having an annual event to collectively honor deceased loved ones. People enjoy creating home altars or community altars to remember loved ones who have passed away. It can be very cathartic, and a way of communicating about family and community histories. It can be grounding, since thinking about the inevitability of death actually makes people appreciate life more. I think Day of the Dead is on the way to being almost as widely known as Halloween, given that celebrations now happen in all 50 states.

In your book, you explain that U.S. Day of the Dead celebrations are inspired by indigenous Mexican traditions, but the holiday has very different meanings for Mexican communities in the US. What are the differences?

RM: The late 1960s and 1970s was a period of radical political activism around the world. In the US, there was the Black civil rights movement, the American Indian movement, the women’s rights movement, the anti-Vietnam War movement, and others. A lot of social change was happening! Ethnic and racial groups who had lived for generations as stigmatized minorities were tired of being treated as second-class citizens vis-à-vis the mainstream Anglo-American population. They had always been told to assimilate in order to become “real” Americans and were made to feel ashamed of their ethnicity or race.

That changed when many young Americans in the 1970s travelled back to their families’ ancestral countries – Italy, Mexico, Ghana, and so forth – to rediscover cultural practices, languages, and histories they hadn’t learned growing up in the US. The term Chicano is a self-identifying term used by Mexican Americans who are politically active in social justice issues. While it had roots in the 1930s, the Chicano Movement really took off in the 1970s (and continues today). It emerged to confront decades of racism in California and the Southwest, where people of Mexican ancestry had long faced segregation in schools, housing, employment, and restaurants as well as harassment and violence. The Chicano Movement was a political movement for equal rights, but it was also a cultural movement that proudly reclaimed Mexican traditions. Celebrating the Day of the Dead was part of that, and my book discusses this process of cultural adoption and transformation. Celebrating an indigenous Mexican ritual in an Anglo-dominant country was an act of political resistance as well as an act of cultural pride.

Today, your book remains one of the few scholarly publications to explain how the rise of Day of the Dead celebrations in the United States emerged as part of Chicano Movement activism. How did this history unfold?

Today, your book remains one of the few scholarly publications to explain how the rise of Day of the Dead celebrations in the United States emerged as part of Chicano Movement activism. How did this history unfold?

RM: In the 1970s, Chicano artists who were born and grew up in the US were interested in reclaiming and celebrating their indigenous Mexican roots. They were tired of the whitewashing of US history. For decades, if Mexican culture was commemorated in the US at all, it was usually the Spanish part of Mexican identity, flamenco dancing, bull fighting, or paella, not indigenous Mesoamerican rituals. So, Chicanos travelled to rural Mexico and brought indigenous traditions to the US via the mediums of visual art, public altar installations, street processions, craft workshops, Aztec danza and other community events. They celebrated Day of the Dead in ways that almost nobody in the US, including most Mexican Americans, had heard of at that time. Only indigenous migrants from central and southern Mexico (who were rare in the US back then) would have practiced elaborate Day of the Dead altar-making traditions. (The US didn't get large migrations from Oaxaca and other heavily indigenous Mexican states until the late 1980s, 1990s, and onwards.)

Based on ethnographic observation, interviewing and news analysis over a period of 20 years, my research tells the story of how Chicano artists created the first public, secular Day of the Dead celebrations in the US in 1972. Since then, Chicano renditions of Day of the Dead have recirculated to Mexico, affecting how Día de los Muertos is celebrated there. For example, Chicano artists in Los Angeles began painting their faces like skeletons during Day of the Dead processions in the mid 1970s, fusing aspects of Halloween with Day of the Dead. This was not previously done in Mexico, but by the late 1990s and 2000s, urban Mexicans were doing this too. Skull face painting is now a major aspect of the celebration in both countries. You never used to see this in indigenous Mexican villages, but with social media, particularly after the 2014-2017 release of popular Hollywood movies like Coco, The Book of Life, and Spectre (which have Day of the Dead themes and characters in “skull face”), you now see skull face painting all over Mexico, including in remote indigenous villages. In my book, I discuss the power of social media and film in the global spread of cultural practices.

You've written that the holiday also provides an example of "the communicative capacity of public cultural rituals in identity construction, community building, education, and political protest." Why is this the case, and why is it important for SC&I students and the American public to understand this?

RM: Public celebrations are always about more than just the stated reason for celebrating. They are ritual opportunities to strengthen the community, reinforce collective identities and values, and reclaim public space to gain wider recognition. For communities that have been marginalized, this is especially important, and these celebrations serve as a form of ritual communication that has new meanings in new contexts.

In the case of ethnic celebrations taking place in the US, these are often important not only for building community but also for expressing political messages. Many Chicano Day of the Dead altar exhibitions have drawn attention to the millions of unnecessary deaths that disproportionately occur to minoritized, low-income people of color, whether because of unsafe working conditions, environmental injustice, violence, war, lack of investment in their communities, or diseases like COVID, which disproportionately devastated Black and Brown populations. Each year, around the country, hundreds of Day of the Dead altars are created in memory of people who died because of sociopolitical issues such as gun violence, police brutality, or hate crimes committed against immigrants, women, or LGBT populations.

In the case of ethnic celebrations taking place in the US, these are often important not only for building community but also for expressing political messages. Many Chicano Day of the Dead altar exhibitions have drawn attention to the millions of unnecessary deaths that disproportionately occur to minoritized, low-income people of color, whether because of unsafe working conditions, environmental injustice, violence, war, lack of investment in their communities, or diseases like COVID, which disproportionately devastated Black and Brown populations. Each year, around the country, hundreds of Day of the Dead altars are created in memory of people who died because of sociopolitical issues such as gun violence, police brutality, or hate crimes committed against immigrants, women, or LGBT populations.

It’s important to understand these dynamics because while official state-supported holidays such as Thanksgiving or the 4th of July serve to promote national unity or patriotism, grassroots commemorations such as indigenous celebrations, pride parades, or Juneteenth, have emerged as forms of resistance to dominant power structures and historical narratives based on colonization, racism, sexism and other forms of injustice.

Understanding the political dimensions of public cultural celebrations helps us see beyond surface-level festivity to understand deeper questions of power, identity, history, inclusion, and resistance, which ultimately helps promote critical thinking and respectful engagement with diverse cultures and histories.

Learn more about the Journalism and Media Studies Department at the Rutgers School of Communication and Information on the website.

Photos: Courtesy of Regina March

This story was published in Rutgers Today on October 24, 2025. "How Day of the Dead Took Root in the United States."

Media coverage:

Phys.Org: "Q&A: How the Day of Dead took root in the United States."

La Republica Espana: "El Día de los Muertos: Una Celebración que Cruzó Fronteras y Transformó Culturas en EE. UU."

Retail Dive: "How Skeletons Transcended Halloween."

NorthJersey.com (The Record): "Celebrate Día de los Muertos 2025 at these events in North Jersey."