A new study examining methods researchers use to identify the gender of people posting content online has found that all of the approaches are flawed, and they systematically undercount or ignore nonbinary users and others who don’t perform their gender in a cis-normative way.

“While binary classification may accurately reflect a majority of the population, people not represented by those categories are consistently under-studied and may face some of the largest disparities in gendered treatment,” the authors wrote.

The study, “Categorizing the non-categorical: the challenges of studying gendered phenomena online,” by Assistant Professor of Communication Sarah Shugars at the Rutgers School of Communication and Information and their colleagues at Northeastern and Harvard Universities, was published in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication in January 2024.

The difficulty researchers have determining the gender of the online posters they are studying has broad implications for research and society. The only way to know someone’s gender is to ask them, but that often isn’t feasible when conducting online research. Scholars instead frequently turn to a practice of “gender inference” -- considering factors like someone’s name or how they look to try to infer gender. This could lead to erroneous conclusions as well as the misgendering or even erasure of some populations.

Across their analyses they also found that nonbinary users and others – both cisgender and transgender – who don’t perform their gender in a cis-normative way are systematically undercounted and frequently misgendered.

Shugars said, “It’s challenging to determine how gender biases manifest online because we often don’t know the gender of online users. For example, if we want to know whether men get more attention for their content or whether women face more online harassment, we first need to guess which users are men or which are women. There are a number of common methods scholars use to tackle this gender inference challenge – for example, researchers might manually inspect accounts to make a judgment as to a user's gender or they might use automated tools to try to infer gender from a user’s name or photo. We compared these methods across a large dataset of social media accounts and found all these measures are imperfect and may reflect different aspects of gendered performance.”

Shugars et al. wrote, “We do not aim to ‘solve’ the unsolvable problem of gender inference. Rather, we have aimed to highlight the empirical implications of gender theory by demonstrating the downstream consequence of common gender inference techniques. Our contribution is in problematizing these measures. Our findings suggest that researchers need to think critically about how they operationalize gender and interpret results based on these measures. Furthermore, our findings consistently suggest the need for more research explicitly focused on the gendered experiences of nonbinary users and those who perform gender outside a cisgender norm.”

To conduct the study, Shugars et al. used a large panel of X (formerly known as Twitter) users matched to U.S. voting records. Looking at a subset of users who were active in 2021, they estimated user gender using multiple common approaches: sex, as recorded in the voter file; use of pronouns or gendered terms; and hand coding of accounts.

“However, researchers must remain aware that perceived gender is not the same as knowing someone’s actual gender and they should interpret their results accordingly. Failure to do so could result in exacerbating gendered disparities both on and offline.”

They compared each of these estimates and further showed how the misgendering of users can have down-stream impacts on questions of online gender disparities.

“For example,” Shugars said, “if accounts are classified using the voter file it appears that ‘men’ get more attention for their content than ‘women.’ This pattern reverses, however, if we estimate gender using pronouns – people who use she/her pronouns tend to get more attention than those who use he/him pronouns. People who use they/them or mixed (he/they) pronouns get even less attention – and, this group represents a population that cannot be identified using the binary genders available in the voter file.”

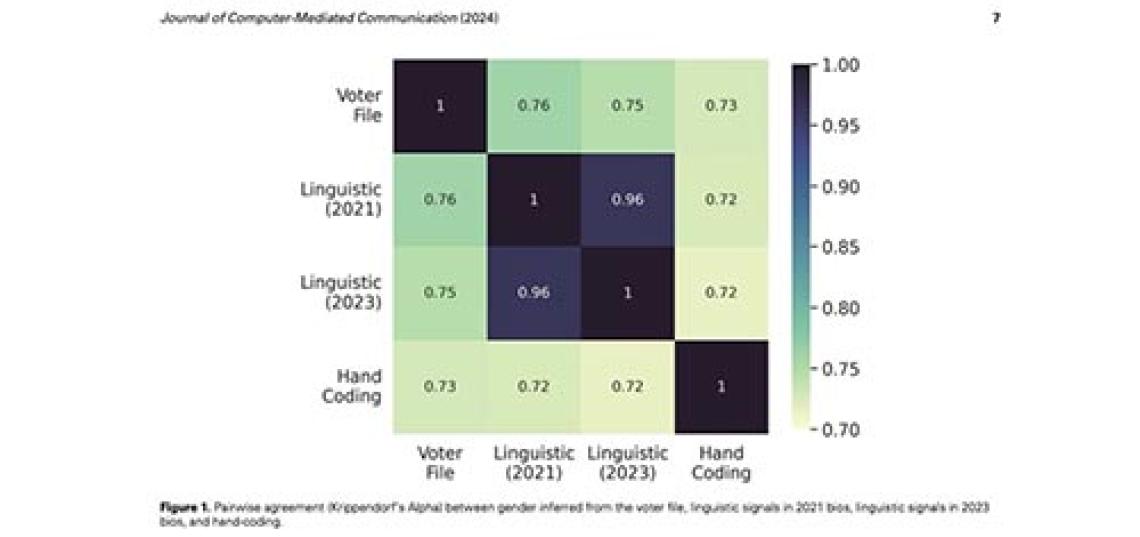

Shugars said hand coding, or manual inspection of accounts, is often held up as the best way to estimate users’ gender, but their study found that this approach is systematically different from measures that more closely reflect a user’s self-report. “For example,” Shugars said, “if someone lists pronouns in their bio those pronouns are often aligned with the gender that person indicated in their voter registration file. But those pronouns are less likely to be aligned with another person’s assumptions about their gender. (See Figure 1 in the paper). We also find that several users change the gendered terms used in their bio over time – sometimes adding or removing gendered signals and sometimes changing the gender they indicate altogether.”

Across their analyses they also found that nonbinary users and others – both cisgender and transgender – who don’t perform their gender in a cis-normative way are systematically undercounted and frequently misgendered.

“This is particularly concerning,” Shugars said, “because we also find evidence to suggest these users may face particular gender-based bias online, but there is very little research examining their experiences.”

The authors also argue that researchers need to be thoughtful about the types of gender-based measurements they employ and how these measures should be interpreted. “For example, hand coding of accounts may still be the most appropriate strategy when investigating how people are treated due to their perceived gender,” Shugars said. “However, researchers must remain aware that perceived gender is not the same as knowing someone’s actual gender and they should interpret their results accordingly. Failure to do so could result in exacerbating gendered disparities both on and offline.”

“In short, the authors wrote, “More work must be done to better analyze and address gaps beyond the gender binary.”

Learn more about the Communication Department and major on the Rutgers School of Communication and Information website.

Image caption: Figure 1. Pairwise agreement (Krippendorf’s Alpha) between gender inferred from the voter file, linguistic signals in 2021 bios, linguistic signals in 2023 bios, and hand-coding. Source: Shugars et al., "Categorizing the non-categorical: the challenges of studying gendered phenomena online."