The French revolted against their monarchy. British sailors revolted against their captain on the royal ship HMS Bounty. Americans wrote the Bill of Rights -- the first ten amendments to the Constitution. Mathematician Jurij Vega calculated pi to the 71st place, a world record. Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, who was enslaved by Jefferson, began their relationship in Paris. All of these events of profound and lasting global significance, as well as many other critical events, took place in the year 1789.

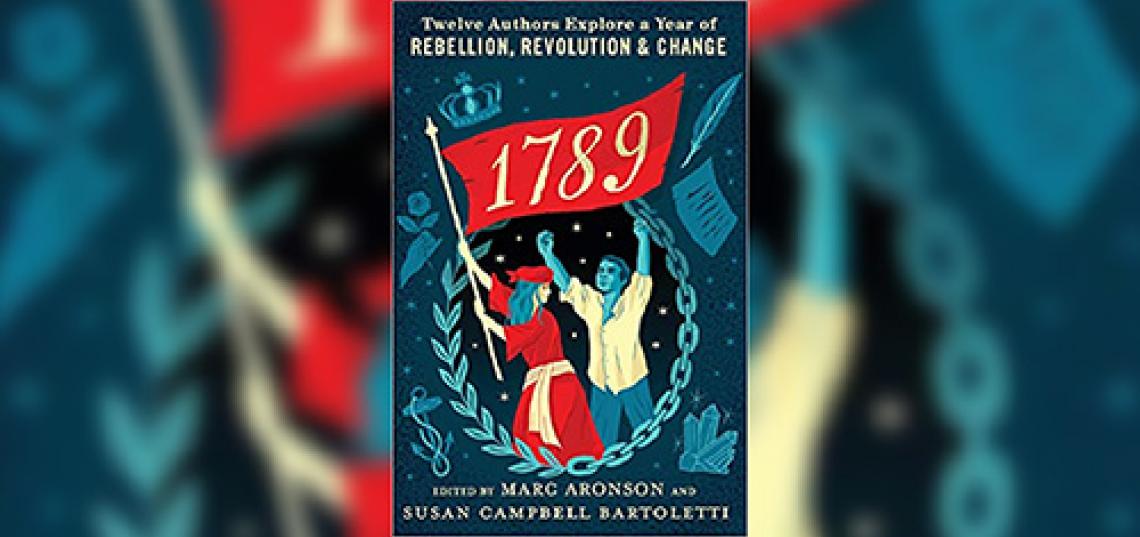

In a new book titled “1789: Twelve Authors Explore A Year of Rebellion, Revolution, and Change,” Associate Professor of Practice Marc Aronson and his co-editor Susan Campbell Bartoletti capture the spirit and lasting impact of the events that took place during this extraordinary year through a collection of chapters written by different authors who are experts on each subject.

“In 1789 there was a sense of the world changing in fundamental ways, and that a new kind of era was being born all over the world,” Aronson said. “It was an era of enslavement, and an era of conflict over human rights that rippled throughout Europe, the Americas, and the Caribbean. It was also the time of new ideas in math and science. All of these forces combined to create both a sense of utopian hope, but also a sense of deep conflict."

“In 1789 there was a sense of the world changing in fundamental ways, and that a new kind of era was being born all over the world,” Aronson said. “It was an era of enslavement, and an era of conflict over human rights that rippled throughout Europe, the Americas, and the Caribbean. It was also the time of new ideas in math and science. All of these forces combined to create both a sense of utopian hope, but also a sense of deep conflict. In both cases, it was as though the same kind of rock was being thrown in a lake which caused ripples, so what seemed to be one thing in one moment, extended, and amplified, and changed. Through the book, we tried to capture 1789 - a year that might feel like 2020 did for many of us, and so far, the way 2021 still does.”

In 1789, Aronson said, the shaking was happening in the English and French worlds, which were then vast colonial empires. In the book, the authors explore the impact these changes had on the lives of “ordinary” citizens, who either worked with historic figures or were part of local movements that ultimately impacted larger, global events.

For example, in one of the chapters, titled “The Queen’s Chemise,” Susan Campbell Bartoletti wrote about Marie Antoinette’s court painter, and the ways the portrait artist’s depictions of the French queen contributed to the resentment many French people felt toward their monarchy, which ultimately contributed to the French Revolution. “The artist, Elisabeth Vigee Le Brun, painted Marie Antionette wearing a chemise, which was not a negligee, but it was painting the queen in what could be seen as an undergarment,” Aronson said. “The unveiling of this portrait was considered the event that undermined Marie Antoinette’s status. People asked, how could she do this? The controversy over the portrait went to the heart of how a powerful woman is seen and what care has to be taken and how she needs to be decorated. We’ve seen something similar in our lifetimes, such as people’s reactions to Hilary Clinton’s white pantsuits. There are many other examples in modern times of the ways powerful women’s wardrobes are scrutinized and judged.”

The chapter titled “The Contradictory King,” by Karen Engelmann, explores another revolt by women that occurred in Sweden in 1789. “This time it was noble women who revolted against their king because he wanted to grant more rights to ‘common’ Swedish people,” Aronson said. “The women who revolted had status anxiety. There are so many twists and turns in 1789. Once people posited that all people are entitled to the same rights, as opposed to believing that only some people were entitled to rights based on the circumstances of their births, the notion of freedom just kept going and it was very hard for those who wanted to control it or stop it to do so.”

Events in the Caribbean in 1789 also illustrate the fight at the time regarding human rights. Referring to the chapter in the book titled “The Wesleyans in the West Indies” by Summer Edward, Aronson said, “In 1789 missionaries brought Christian ideas to the West Indies and the Caribbean, which the planters didn’t like, because if their enslaved people converted to Christianity, then what right did they, as Christian owners, have to enslave them? So once these ideas - that people have rights - began, well, then the discussion was, which people? That’s a question we are still asking now. Once you open that question, it’s hard to close it.”

"Here is Jefferson, a key writer of the Declaration of Independence, who also formulated some of the ideas of the Declaration of the Rights of Man. He was a far-thinking guy, who was also a slave master. All of these conflicts came together in the question of his relationship with Sally Hemings and what it would be like."

Aronson wrote a chapter called “The Choice” about Thomas Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemings. Aronson said his chapter highlights the importance of understanding their relationship in the context of the time when it took place. Sally and her family were enslaved, that is, legally owned, by Jefferson. But they were also Jefferson's relatives, and on both sides the families had deep bonds. Sally Hemings was the half-sister of Jefferson’s wife Martha Jefferson (who had died by the time Sally and Thomas began their relationship in Paris in 1789). Sally and Martha shared the same father.

“The chapter portrays the cross-currents of the Jefferson family, and the ways the relationships between people who were Black and white, enslaved and free, were entangled and were very deep. When we look at the period of our American past, we need to understand it not as part of the old-fashioned hero-worship of the founding fathers, or the later condemnation of the founding fathers. We need to take the next step and move past the ‘heros’ and ‘villains’ narrative in order to understand the complexity of their moment and the cross-currents of the time. I think that may help us see our own time in greater perspective.

“I would really urge people who want to think about the present and past of our country, to think about the fact that Black and white people intermixed from very early on in our history, often through rape and forced relations, but our fates were and are entwined. We have to understand the abuses of power, but also understand how entangled we were and are with one another.”

Aronson said he relied on the work of Harvard University historian Annette Gordon-Reed as a source of information while writing about Hemings and Jefferson. She wrote the book “The Hemingses of Monticello, An American Story.”

We know Jefferson wasn’t perfect, but it also seems important, especially in light of today’s conflicts, to understand Jefferson’s conflicts. So through this chapter, that’s what I did.”

“It’s very important to understand that in 1789 their relationship was not an aberrant, secret thing,” Aronson said. “The more we look at DNA, and the more people examine their family records, it’s very clear that relationships like theirs were very prevalent in 1789. Life was full of these incredible conflicts. Here is Jefferson, a key writer of the Declaration of Independence, who also formulated some of the ideas of the Declaration of the Rights of Man. He was a far-thinking guy, who was also a slave master. All of these conflicts came together in the question of his relationship with Sally Hemings and what it would be like.

“This is why I wanted to write the chapter about them. It seems to me that their relationship provides a window through which we can look to try to understand those times and debate them. I have talked to people about our book 1789 since it was published, and I think people like pondering these questions. We know Jefferson wasn’t perfect, but it also seems important, especially in light of today’s conflicts, to understand Jefferson’s conflicts. So through this chapter, that’s what I did.”

More information about the Library and Information Science Department at the Rutgers School of Communication and Information is on the website.

Image: Courtesy of Marc Aronson