SC&I Teaching Professor of Library and Information Science Nancy Kranich is a tireless champion of the public’s information rights. As a former president of the American Library Association and chair of its Intellectual Freedom Committee, Kranich has spoken out against censorship, filtering, privatization, and other attempts to limit public access to vital information.

Much of Kranich’s library career was based at New York University, where, as Associate Dean of Libraries, she managed NYU’s libraries, press, and media services. Kranich is a member of the Board of Trustees of the Highland Park, NJ, Public Library and the editorial board of Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy. She is also Treasurer of the National Security Archive in Washington and judges Project Censored's Most Underreported Stories of the Year. Internationally, she has advanced libraries and democracy in Eastern Europe and promoted universal service and information commons in France, China, Mexico, and Taiwan.

SC&I spoke with Kranich about the impact of book challenges and banning on public and school libraries, librarians, library patrons (particularly children and young adults), and democracy.

Kranich is a former president of the American Library Association and chair of its Intellectual Freedom Committee.

SC&I: How much has book banning increased in recent years?

NK: If librarians pulled every book in their collections that somebody has objected to, libraries would have no books on their shelves. Much of the current discourse on book banning is focused on the question: What information will schools make available to young people?

Countries across the globe have banned books for thousands of years, so book banning is not new. Even in the United States, where we are protected by the First Amendment, there are boundaries, many of which are contested, particularly recently.

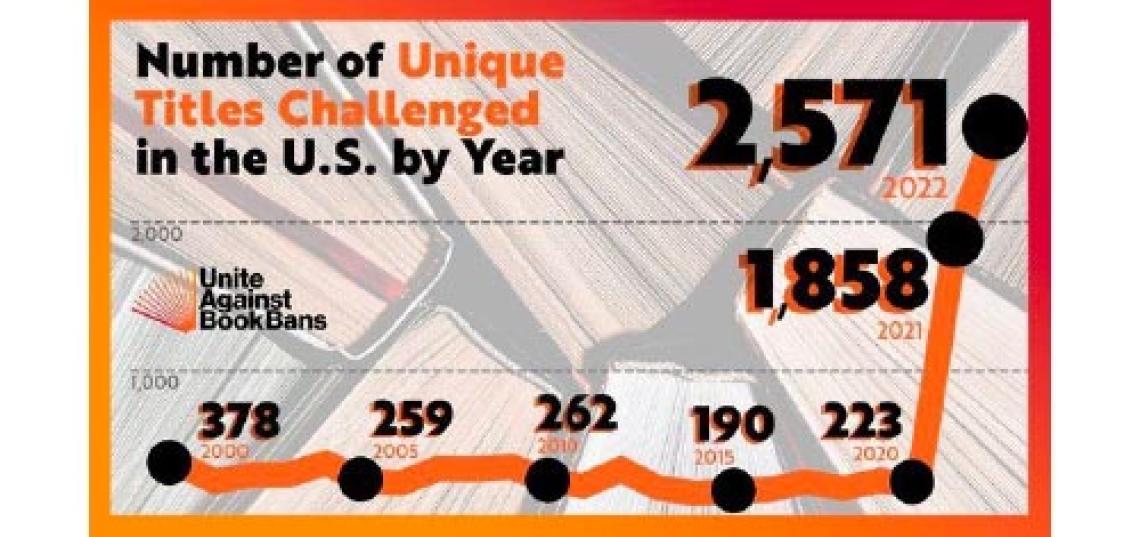

The American Library Association has collected and documented challenged books for the last 25 years (at least), and since I began teaching Intellectual Freedom 17 years ago, every year I've kept a record with my students of the books banned, their themes and overall trends. For the last 25 years, up until 2021, about 300 to 500 books were reported challenged a year. We in the library field think this is probably at best half, if not less than half, of what actually has taken place. But those numbers reflect what people have reported. And suddenly, we're up in the thousands during the last two years. In fact, in 2022 there was a 40% increase in challenged books over 2021, the year when numbers first skyrocketed. This was a huge increase – nearly threefold over what we'd experienced previously.

When we call them banned books, we refer to books that are challenged whether or not they ultimately get banned. Books usually are not banned, because people protest pulling them off of library shelves. But if they've been challenged with the possibility of being moved to a restricted area, or actually taken out of the library collection, then they are considered banned. All books that are challenged are not banned, thanks to advocates stepping forward to protect them and librarians following good policy and practice when responding to concerns.

"Being a good librarian means being well prepared to provide library collections and services under the First Amendment of the United States that are in keeping with the laws and practices of openness, fairness, and free expression. Our motto these days is ‘Free People Read Freely.’"

SC&I: What kinds of books are generally challenged or banned?

NK: LGBTQ books have been on the rise of recent challenges; books about sexuality; obscenity; and books with obscene words are also targets. Although some books about race and ethnicity issues were challenged in the past, rates of these targeted items have skyrocketed recently. Most of the books we're seeing challenged, since the beginning of the days we first started documenting, are books written for children or young adults.

SC&I: What impact do book challenges have on education, society, and democracy?

NK: Every country is different. No other country has a First Amendment as we do. So, we're not only the global model for democracy, but also we recognize that open discourse and access to ideas is what makes democracy work. And if we don't have that access – if we start to suppress ideas – we start to create the kind of repressed society that we oppose as a society.

Just as important, though, is understanding what happens in school libraries when one of these books is not available. Many of us may think of book reading as something we do for fun, or leisure, or for required reading. But we also need to realize that books are lifelines, particularly for young people searching for answers.

Books are also the way we start to understand experiences beyond our own, but that others live. Books help us build empathy and an understanding of the world and the diverse people we encounter.

". . . being a librarian means committing themselves to an ideal of what democracy is all about. Part of living in a democracy means respecting each other's differences and the right of all people to choose for themselves what they and their families read."

SC&I: Can public and school libraries play a role in addressing or countering the effort by some Americans to ban books?

NK: One of the things I tell my students about the First Amendment is that it protects minority rights, and it also protects against the tyranny of the majority. But now we're also learning about – and a new book has just come out about it – the tyranny of the minority. In this country, we can see a small minority takeover in terms of book bans and challenges.

Now that book banning is such a hot issue, pollsters are asking about the issue, finding as many as 90% of the American public against banning books. And even the lowest numbers are in the seventies. So what's going on here? We've got the tyranny of the minority.

For example, in the U.S., The American Library Association documents book challenges, as does Pen America (the writer's group), GLAAD (an LGBTQ activist group in New York), the ACLU, and many other groups. A study by the Washington Post found only 11 people behind most of the book challenges all around the country. So, a small number of people can be very influential in triggering reactions.

We need an equal and opposite reaction to book challenges. In other words, people need to be willing to stand up and be brave, and say ‘no’ to these actions, and say ‘yes’ to why these materials are so important – to history, to our education, to helping young people, and also to our democracy. And that’s exactly what is happening. All types of groups are emerging who are speaking out for the right to read.

SC&I: What does the ‘tyranny of the minority’ phenomena mean for public and school libraries?

NK: First and foremost, libraries are the front door to the First Amendment in every community. They are where free expression is located and insured for everyone who resides there. They play such an important role, in a way that no other institution does. No other institution stands, as its core value, for the idea of free expression and open access to ideas. Libraries are, first and foremost, the front line on this issue. So that's number one.

Number two, that means that librarians must be well-equipped to deal with any kinds of challenges they come across. Lots of challenges that parents and other local residents raise are reasonable. They see what their kids are reading, or they read something, and they think, I really don't like what's being said. This offers a perfect opportunity for a well-trained librarian to explain to them why, even though they object to a book, that it’s important to consider the work as a whole and retain it on the shelf for others to choose. Every book challenge is not from a hostile segment of the community or even from people that don't even live in the community, or those out to attack public institutions. Recently, though, surges in book challenges reflect organized efforts by outside 'parental rights' groups eager to have their own preferences prevail and to score political points.

"That makes our profession – while perhaps more dangerous because of the recent rash of book challenges – more appealing because the public sees now how important we are to ensuring these sacred rites."

SC&I: As a SC&I faculty member, how do you educate future librarians to address book bans, censorship, and intellectual freedom?

NK: I think the class is a real draw because students realize they need to be well-equipped to deal with book challenges as part of being a librarian today. The class teaches future librarians good policy-making and practice that guides their work and interprets the importance of building and maintaining diverse collections that reflect the interests of everyone in the community. Not every book is right for everyone but everyone deserves access to a book that is right for them. Parents have a right to select items for their children but should not impose their beliefs on other people’s children. At a moment of great concern about children’s academic performance and their declining love of reading, one thing is clear: Kids read more – and more enthusiastically – when they’re allowed to choose their own books!

It's the school librarians who are getting beaten up the most. We try to teach them that they need to be prepared. We teach them how to select a wide array of materials, how to catalog them by describing them in a way that's accurate, fair, and neutral, and how to guide their users to materials well suited to their interests and preferences. Being a good librarian means being well prepared to provide library collections and services under the First Amendment of the United States that are in keeping with the laws and practices of openness, fairness, and free expression. Our motto these days is ‘Free People Read Freely.’

And that's exactly what we want to infuse in their understanding of what this is about. It's not just about being somebody who buys books and makes them available. There's something much deeper in these core values, and that's what we teach in librarianship generally. And hopefully, our students learn that this is about far more than checking out books. And that being a librarian means committing themselves to an ideal of what democracy is all about. Part of living in a democracy means respecting each other's differences and the right of all people to choose for themselves what they and their families read.

And I think that makes our profession – while perhaps more dangerous because of the recent rash of book challenges – more appealing because the public sees now how important we are to ensuring these sacred rites.

Learn more about the Library and Information Science Department at the School of Communication and Information on the website.

Image courtesy of Nancy Kranich. Source: National Coalition Against Censorship.